Using AI Skills for Reverse Engineering

I’ve been exploring skills within the context of AI lately. In the research literature, skills are reusable, temporally extended behaviors (policies), often formalized as options, that an agent can invoke as a single unit to accomplish a subtask, enabling complex behavior through composition and reuse of these modular procedures.

Skills provide an opportunity to speed up reverse engineering tasks through repeatable, analyst-in-the-loop playbooks that standardize inputs/outputs, enforce guardrails (like “no invention”), and keep the workflow scoped to the moment it’s needed.

There are several examples of how different AI providers use skills within their tools:

OpenAI Codex — Skills are directories with a required SKILL.md; Codex preloads only skill metadata and loads full instructions only when it decides to use the skill (progressive disclosure).

Claude Code — Skills are bundled inside plugins; plugins are discovered/installed via plugin marketplaces and can include skills alongside agents, hooks, and MCP servers.

GitHub Copilot — Agent Skills are folders of instructions, scripts, and resources that Copilot loads when relevant to improve performance on specialized tasks across Copilot surfaces.

For this blog entry, I’m concentrating on working with OpenAI’s Codex, with different AI providers planned for some future blog entries.

Getting Started

For this post, I wanted to focus on something simple: building a repeatable way to “load the right playbook” during reverse engineering without having to rewrite the same scaffolding every time.

I’m treating skills as small, opinionated workflow packages. Each one has a clear purpose, required inputs, guardrails, and a predictable output format. The goal isn’t to replace analysis—it’s to make the parts that are already repeatable feel more consistent.

A big reason this works well with Codex is progressive disclosure: Codex starts by loading only the skill metadata, and only pulls the full SKILL.md instructions when it decides the skill is relevant. That keeps the “library of skills” from bloating context on every run.

Environment Details

For this testing, I used a dedicated reverse engineering VM so I could keep things isolated and reproducible.

Here’s what I’m running for reference:

· Virtualization: VMWare

· Guest OS: Windows (FLARE-VM Image)

FLARE-VM is essentially a curated Windows reverse engineering toolkit deployed via install scripts (built around Chocolatey and Boxstarter). The main reason I like it for posts like this is that it’s easy to rebuild from scratch and the baseline toolset is familiar.

For this blog entry, FLARE-VM also gives me a safer default posture for testing (VM boundary + controlled execution) while still having the tools I actually use when working through samples.

Codex Install

I’m using OpenAI Codex CLI for this post since it’s built to work directly inside a repo and can load skill content when needed.

Installation is straightforward:

· Install Codex CLI via npm: npm i -g @openai/codex

· Launch it with: codex

· On first run, sign in with your ChatGPT account or use an API key (depending on how you’re running it)

OpenAI’s docs also call out that Codex can inspect your repository, edit files, and run commands—so it fits nicely with iterating on skills in-place.

WARNING: I used an virtual machine that was safe to have online for a bit to do the install. If you’re using a analysis environment that is not capable of that by any means, consider doing a copy of the files. I haven’t experimented with this yet, so I don’t have a lot of confidence on how to do it. Feel free to add any comments to the blog if you do!

All of the skills I’m working on live in my public repo here: https://github.com/hackersifu/reverse-engineering-skills

The structure is intentionally simple: a skill is a folder, and the core definition lives in a SKILL.md file. For Codex, skills are designed to be directories with a required SKILL.md, and the tool can load skill metadata and pull the full instructions only when it needs them.

That “only load what’s needed” model matters when you start collecting more skills, because it keeps the agent from dragging the entire library into context every time.

Creating our RE Skills

I started with two skill candidates:

Unpacking (re-unpacker)

IOC extraction (re-ioc-extraction)

I picked these first because they’re the kind of tasks I end up repeating across samples, regardless of malware family:

Unpacking: packed samples are common, and even a basic “is it packed?” triage loop benefits from consistency (strings density, sections, entropy hints, packer signatures, and a defensible next-step plan).

IOC extraction: it’s a straightforward early test case that still produces genuinely useful output (defender-ready indicators with evidence) without requiring deep program understanding on day one.

The part I care about most is that both skills are written to produce artifacts I’d actually want at the end of an investigation:

re-unpacker produces an unpacking plan + unpacking report and stays “static-first,” only going dynamic if an engineer explicitly approves running the sample in a controlled sandbox/VM.

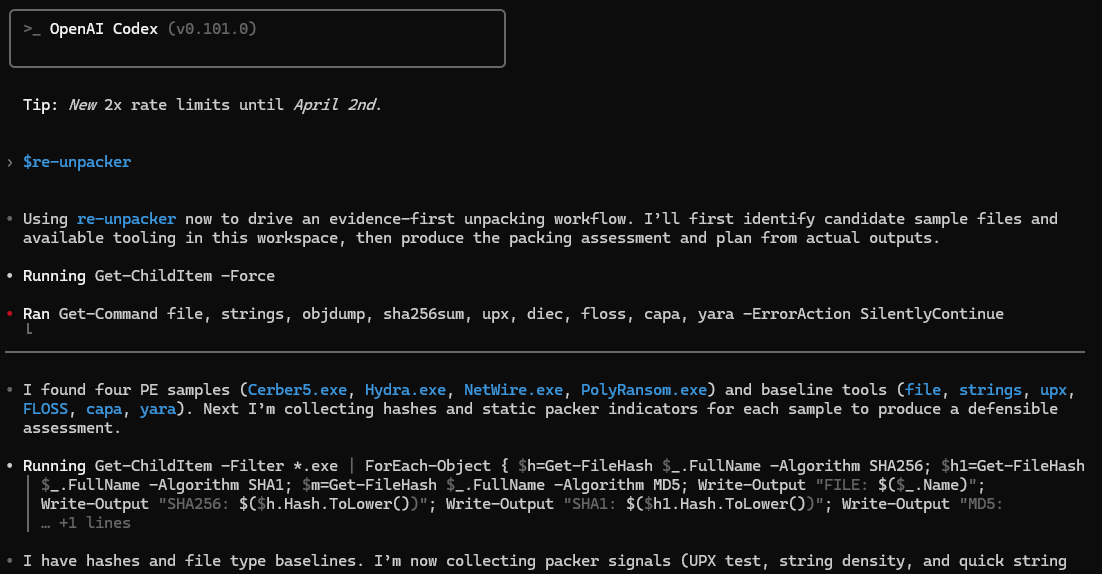

re-unpacker - Initial Output

re-ioc-extraction produces two outputs every time: a Markdown IOC table and a structured YAML list, with strict “traceable evidence only” rules (no enrichment, no guessing, no validation).

That guardrail pattern is intentional: if execution is required, the skill should pause and force a decision instead of marching forward.

Running Tests on Actual Malware (what you ran + how you kept it safe)

For testing, I used four different samples.

Important boundary: I treated this as defensive triage, not detonation. The skills are written to stay static unless an engineer explicitly approves controlled execution, and I kept the environment VM-scoped to reduce blast radius.

The workflow I followed was basically:

Run the skill in “safe mode” first (tool check + static triage).

Capture artifacts (hashes, file type, strings outputs, capability hints).

Iterate on the skill when failures were caused by assumptions (not because the sample was “hard”).

Iteration Details

The details of the first run are included here:

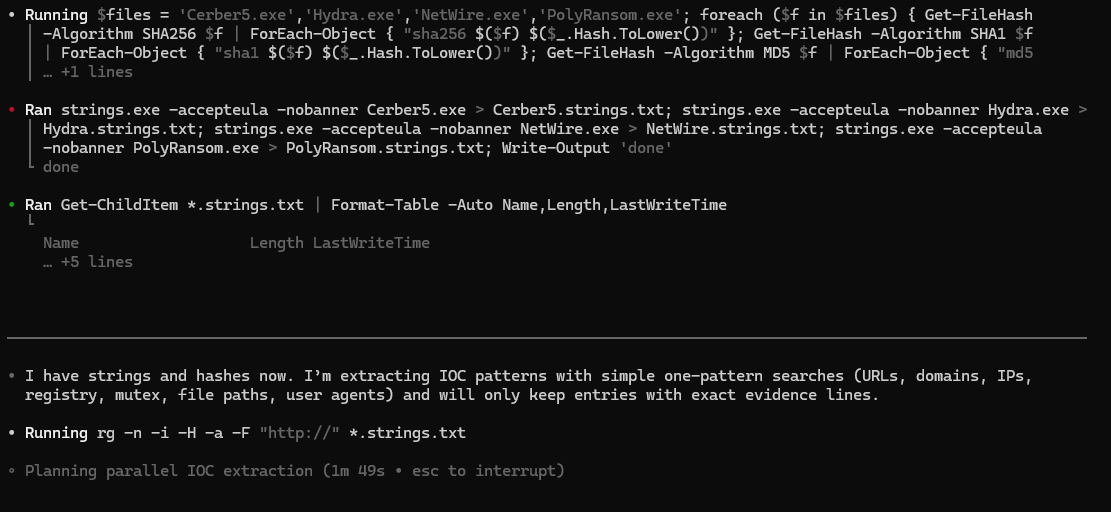

• Running $files = 'Cerber5.exe', 'Hydra.exe', 'NetWire.exe', 'PolyRansom.exe'; foreach ($f in $files) { Get-FileHash

-Algorithm SHA256 $f | ForEach-Object { "sha256 $($f) $($_.Hash.ToLower())" }; Get-FileHash -Algorithm SHA1 $f

| ForEach-Object { "sha1 $($f) $($_.Hash.ToLower())" }; Get-FileHash -Algorithm MD5 $f | ForEach-Object { "md5

… +1 lines

• Ran strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner Cerber5.exe > Cerber5.strings.txt; strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner Hydra.exe >

Hydra.strings.txt; strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner NetWire.exe > NetWire.strings.txt; strings.exe --accepteula

--nobanner PolyRansom.exe > PolyRansom.strings.txt; Write-Output 'done'

done

• Ran Get-ChildItem *.strings.txt | Format-Table -Auto Name,Length,LastWriteTime

Name Length LastWriteTime

… +5 lines

• I have strings and hashes now. I’m extracting IOC patterns with simple one-pattern searches (URLs, domains, IPs,

registry, mutex, file paths, user agents) and will only keep entries with exact evidence lines.

• Running rg -n -i -H -a -F "http://" *.strings.txt

• Planning parallel IOC extraction (1m 49s • esc to interrupt)

…

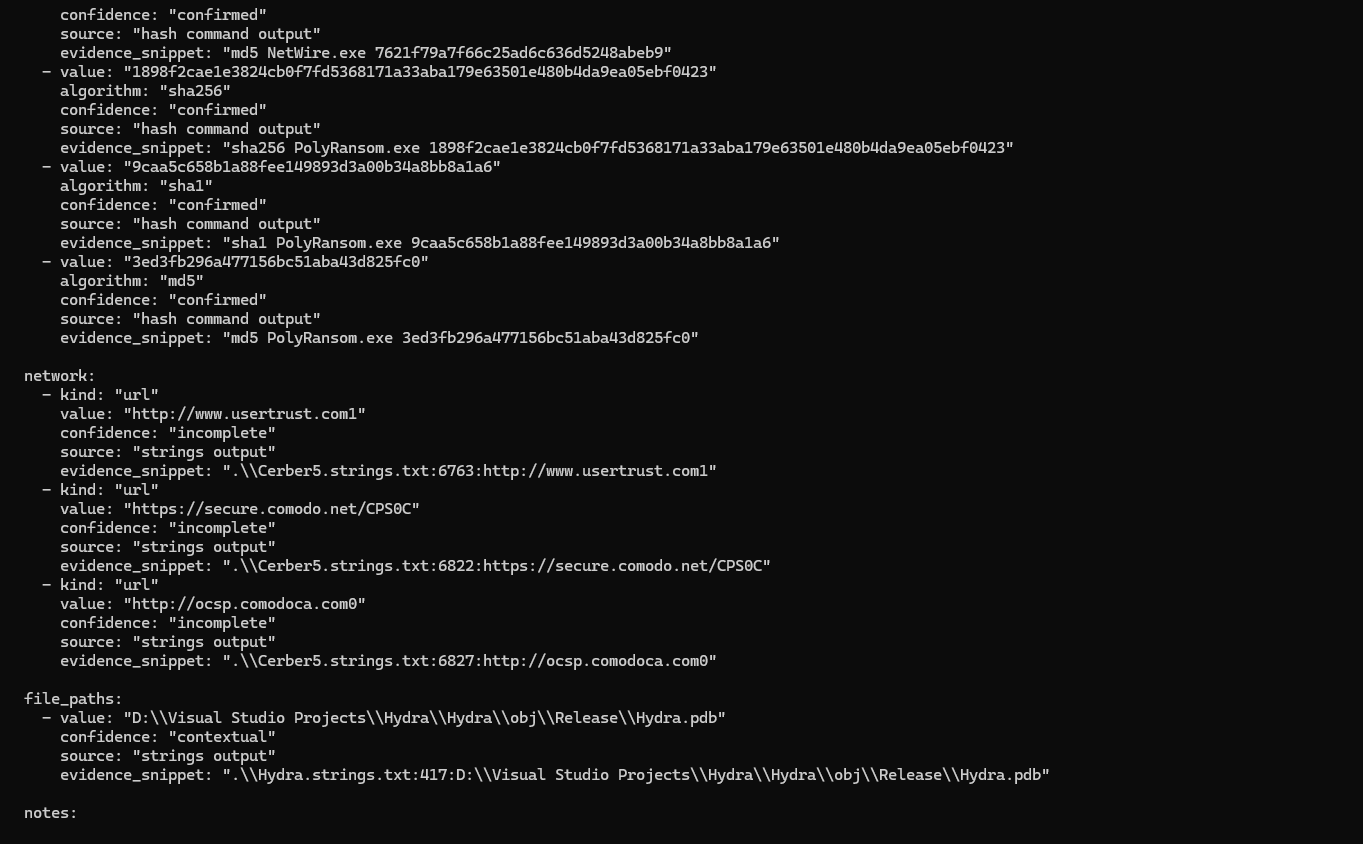

network:

- kind: "url"

value: "http://www.usertrust.com]"

confidence: "incomplete"

source: "strings output"

evidence_snippet: ".\\Cerber5.strings.txt:6763:http://www.usertrust.com]"

- kind: "url"

value: "https://secure.comodo.net/CPSOC"

confidence: "incomplete"

source: "strings output"

evidence_snippet: ".\\Cerber5.strings.txt:6822:https://secure.comodo.net/CPSOC"

- kind: "url"

value: "http://ocsp.comodoca.com0"

confidence: "incomplete"

source: "strings output"

evidence_snippet: ".\\Cerber5.strings.txt:6827:http://ocsp.comodoca.com0"

…

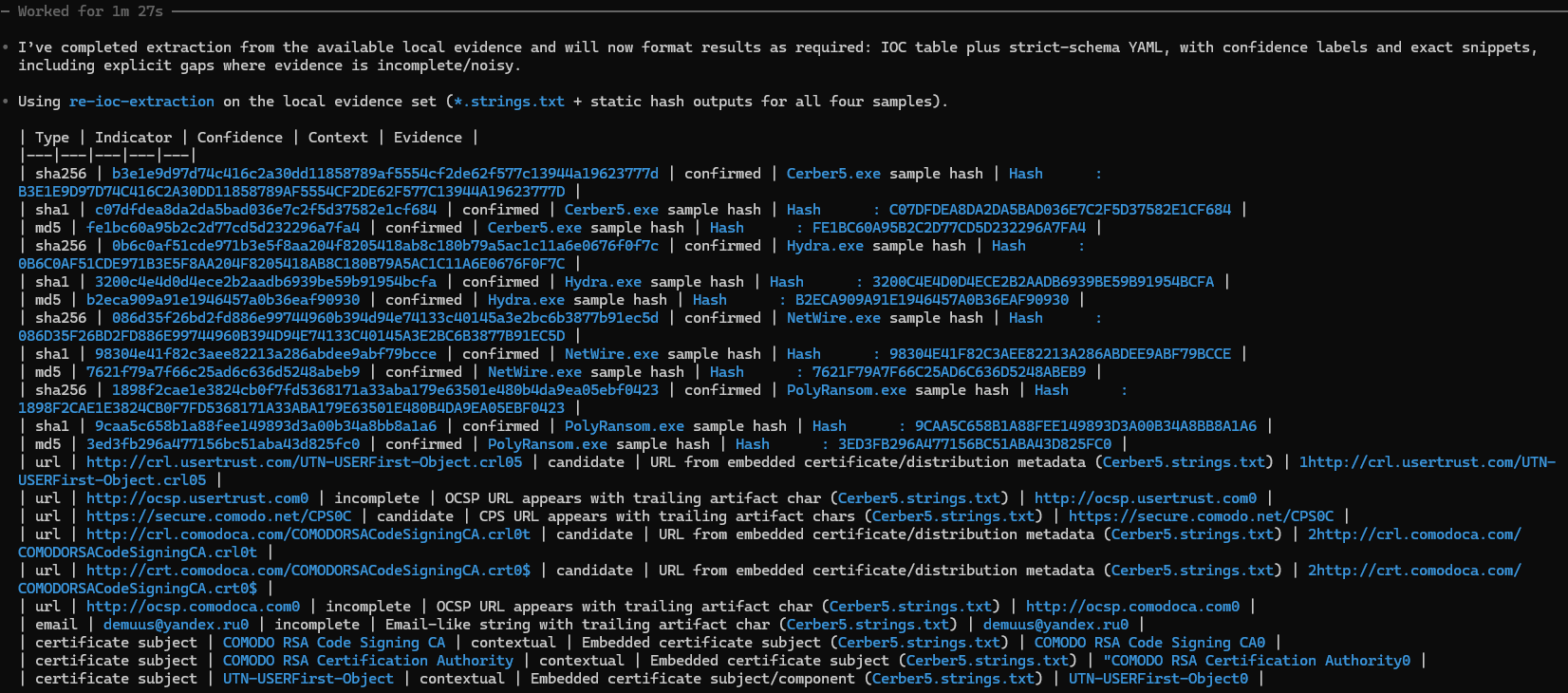

• I’ve completed extraction from the available local evidence and will now format results as required: IOC table plus strict-schema YAML, with confidence labels and exact snippets,

including explicit gaps where evidence is incomplete/noisy.

• Using re-ioc-extraction on the local evidence set (*.strings.txt + static hash outputs for all four samples).

| Type | Indicator | Confidence | Context | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sha256 | b3e1e9d97d74c416c2a30dd11858789af5554cf2de62f577c13944a19623777d | confirmed | Cerber5.exe sample hash | Hash |

…

| url | http://www.usertrust.com] | incomplete | OCSP URL appears with trailing artifact char (Cerber5.strings.txt) | http://www.usertrust.com] |

| url | https://secure.comodo.net/CPSOC | candidate | CPS URL appears with trailing artifact chars (Cerber5.strings.txt) | https://secure.comodo.net/CPSOC |

| url | http://ocsp.comodoca.com0 | incomplete | OCSP URL appears with trailing artifact char (Cerber5.strings.txt) | http://ocsp.comodoca.com0 |

…

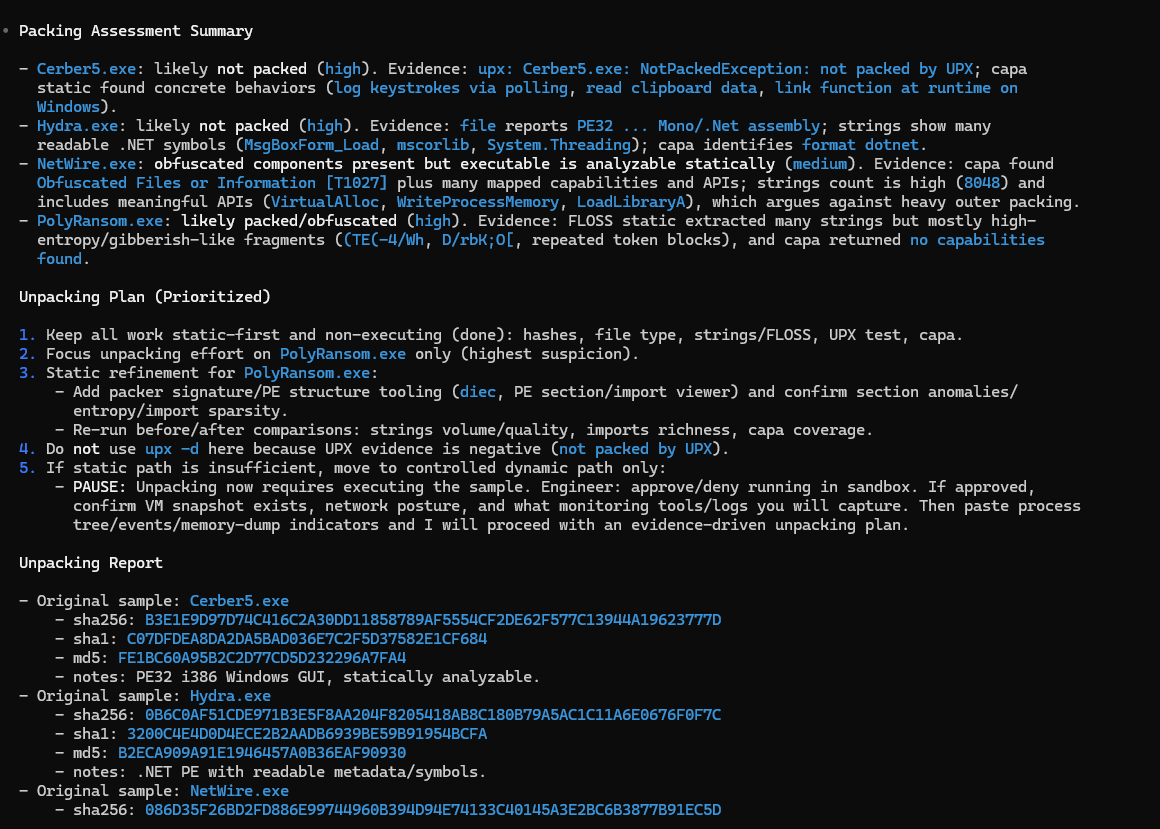

• Packing Assessment Summary

- Cerber5.exe: likely not packed (high). Evidence: upx: Cerber5.exe: NotPackedException: not packed by UPX; capa

static found concrete behaviors (log keystrokes via polling, read clipboard data, link function at runtime on

Windows).

- Hydra.exe: likely not packed (high). Evidence: file reports PE32; Mono/.Net assembly; strings show many

readable .NET symbols (MsgBoxForm_Load, mscorlib, System.Threading); capa identifies format dotnet.

- NetWire.exe: obfuscated components present but executable is analyzable statically (medium). Evidence: capa found

Obfuscated Files or Information [T1027] plus many mapped capabilities and APIs; strings count is high (8048) and

includes meaningful APIs (VirtualAlloc, WriteProcessMemory, LoadLibraryA), which argues against heavy outer packing.

- PolyRansom.exe: likely packed/obfuscated (high). Evidence: FLOSS static extracted many strings but mostly high-

entropy/gibberish-like fragments (CTE(-4/wh, D/rbk0, repeated token blocks), and capa returned no capabilities

found.

Unpacking Plan (Prioritized)

1. Keep all work static-first and non-executing (done): hashes, file type, strings/FLOSS, UPX test, capa.

2. Focus unpacking effort on PolyRansom.exe only (highest suspicion).

…

5. If static path is insufficient, move to controlled dynamic path only:

- PAUSE: Unpacking now requires executing the sample. Engineer: approve/deny running in sandbox. If approved,

confirm VM snapshot exists, network posture, and what monitoring tools/logs you will capture. Then paste process

tree/events/memory-dump indicators and I will proceed with an evidence-driven unpacking plan.

I didn’t get this perfect on the first run—and that’s kind of the point.

The first pass surfaced the “real world friction” you hit when you try to standardize workflows across environments: tools weren’t always present (or weren’t the variant I expected), PowerShell quoting/globbing did what PowerShell does, and long one-liners were fragile.

To make this concrete, here’s what “working through the friction” looked like in practice.

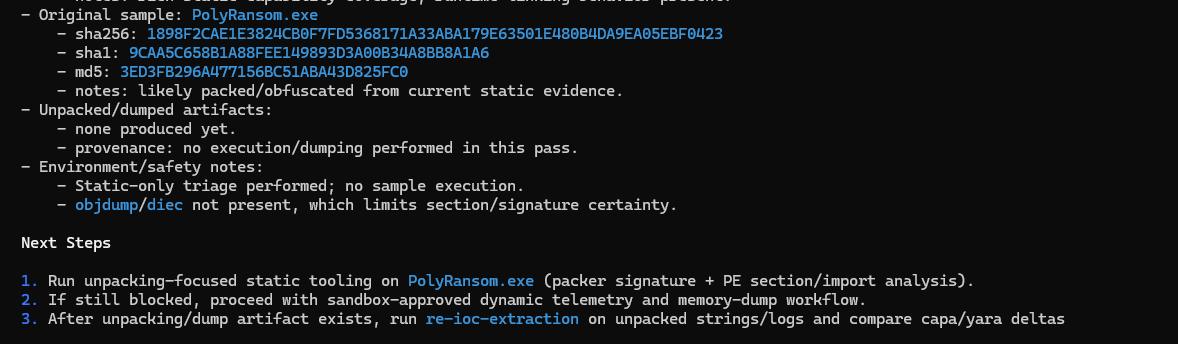

1) I started by forcing a clean baseline: hashes + strings, across all samples

• Running $files = 'Cerber5.exe', 'Hydra.exe', 'NetWire.exe', 'PolyRansom.exe'; foreach ($f in $files) { Get-FileHash

-Algorithm SHA256 $f | ForEach-Object { "sha256 $($f) $($_.Hash.ToLower())" }; Get-FileHash -Algorithm SHA1 $f

| ForEach-Object { "sha1 $($f) $($_.Hash.ToLower())" }; Get-FileHash -Algorithm MD5 $f | ForEach-Object { "md5

… +1 lines

Why this mattered: this is the “boring” part, but it anchors everything else. Once hashes exist, the rest of the workflow can be repeatable and defensible (and it keeps you honest about exactly which artifacts you’re discussing).

• Ran strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner Cerber5.exe > Cerber5.strings.txt; strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner Hydra.exe > Hydra.strings.txt; strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner NetWire.exe > NetWire.strings.txt; strings.exe --accepteula --nobanner PolyRansom.exe > PolyRansom.strings.txt; Write-Output 'done' done

Why this mattered: this is where I hit the “environment reality.” strings.exe is great, but it’s also one of those tools where non-interactive flags matter. Baking --accepteula --nobanner into the repeatable workflow keeps it from stalling you later (especially inside automation).

• Ran Get-ChildItem *.strings.txt | Format-Table -Auto Name,Length,LastWriteTime

Why this mattered: simple verification step. When skills are driving commands, I want a quick “did we actually create the artifacts?” sanity check before I start searching patterns.

re-ioc-extractor - Command output

2) Then I switched to strict, one-pattern searches — and kept only exact evidence lines

• I have strings and hashes now. I’m extracting IOC patterns with simple one-pattern searches (URLs, domains, IPs, registry, mutex, file paths, user agents) and will only keep entries with exact evidence lines.

Why this mattered: this line is basically the “contract.” It prevents the model (and honestly, me too) from drifting into enrichment, assumptions, or “it probably means X.” The goal is artifacts with provenance, not guesswork.

• Running rg -n -i -H -a -F "http://" *.strings.txt

Why this mattered: this is where the PowerShell/Windows ergonomics started to show. Pattern searches are simple, but the details (quoting, globs, file filters) are where you can lose time across runs.

• Planning parallel IOC extraction (1m 49s • esc to interrupt)

Why this mattered: early runs were noisier because parallelism + shell quirks can amplify small mistakes. Later runs got better as the workflow became more conservative and PowerShell-safe.

3) By the later runs, the output became stable: structured artifacts with explicit confidence + evidence

This is the point where the skill stopped “freestyling” and started behaving like a repeatable playbook:

• I’ve completed extraction from the available local evidence and will now format results as required: IOC table plus strict-schema YAML, with confidence labels and exact snippets, including explicit gaps where evidence is incomplete/noisy.

Why this mattered: “explicit gaps” is the difference between defensible output and convincing output. If something looks incomplete (like certificate URLs with trailing junk), the skill calls it out instead of pretending it’s clean.

You can see that play out directly in the YAML output:

network:

- kind: "url"

value: "http://www.usertrust.com]"

confidence: "incomplete"

source: "strings output"

evidence_snippet: ".\\Cerber5.strings.txt:6763:http://www.usertrust.com]"

Why this mattered: the trailing ] is exactly the kind of thing that can slip into a report if you don’t force evidence + confidence labeling.

And the table format makes it easy to scan what matters quickly:

• Using re-ioc-extraction on the local evidence set (*.strings.txt + static hash outputs for all four samples).

Why this mattered: it makes the input boundary explicit — which keeps the workflow reproducible.

4) The “boring” iteration actually showed up in the stats

After each run, I tightened the workflow in a very boring way: reduce assumptions, simplify commands, add preflight checks, and prefer patterns that survive copy/paste across Windows shells.

You can see the effect in the run stats: by run 3, re-unpacker dropped from 31 commands / 20 errors down to 9 commands / 4 errors — mostly because the skill stopped fighting the environment and started using a smaller set of reliable, repeatable steps.

Collecting Statistics

For iterating on our work, I created a “stats” prompt to run through after each skills invocation:

Stats Prompt:

Generate a short “Codex Run Stats” summary for this session using ONLY the observable run log (timestamps, approvals, commands executed, and errors); if any metric can’t be derived exactly, mark it as “unknown” and (optionally) give a conservative estimate with assumptions—then output the summary using the template below.

## Codex Run Stats (Short Summary)

- **Session / Run ID:** <id-or-timestamp>

- **Skill(s) used:** <re-ioc-extraction | re-unpacker | ...>

- **Environment:** <FLARE-VM / host / cloud shell> | **Permissions mode:** <read-only / standard / auto> :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

### Performance

- **Total analysis time:** <HH:MM:SS>

- **Total samples analyzed:** <N>

- **Total commands run:** <N>

- **Total errors:** <N>

- **Blocked by approvals:** <N> :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

- **Command failures (exit != 0):** <N>

- **Other (parsing/format/etc.):** <N>

### Analyst time saved (estimated)

- **Estimated analyst time saved:** <X minutes> (≈ <Y%> of total)

- **Method:** sum of (baseline manual time per step) − (actual time with Codex) across repeated steps :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

- **Assumptions:** <e.g., “hash+file+strings+sections normally ~12 min/sample; with Codex ~4 min/sample”>

### Notes (optional)

- **Top time sinks:** <e.g., tool installs, missing utilities, quoting issues>

- **Most helpful outputs:** <e.g., clean IOC YAML, unpacking plan, evidence excerpts>

- **Next improvement:** <e.g., add tool check, tighten schema, reduce command count>

Results

Here’s the short version of what happened across runs:

| Skill | Run | Samples | Commands | Estimated wall-time |

|---|---:|---:|---:|---:|---|

| re-unpacker | 1 | 4 | 31 | 20 | ~00:10:10 |

| re-unpacker | 2 | 4 | 20 | 10 | ~00:02:27 |

| re-unpacker | 3 | 4 | 9 | 4 | ~00:01:05 |

| re-ioc-extraction | 1 | 27 | 15 | ~00:04:25 |

| re-ioc-extraction | 2 | 4 | 39 | 19 | |

| re-ioc-extraction | 3 | 4 | 31 | 17 | ~00:05:35 (lower bound) |

A few things stood out:

Iteration actually reduced operational noise. The biggest wins weren’t “smarter analysis”—they were fewer broken commands and fewer environment-dependent assumptions.

The unpacker skill stabilized fast. Once the toolchain checks and “static-first plan” were in place, it became a consistent triage playbook instead of a one-off checklist.

IOC extraction is deceptively tricky on Windows shells. The guardrails and output format were solid, but the evidence collection step (strings → pattern searches) needed PowerShell-safe defaults to avoid repeated “exit 1” cases—especially because tools like ripgrep return exit code 1 when there are no matches.

Even with retries and failures, the skills still did what I wanted: produce repeatable artifacts (hashes/strings outputs, structured IOC YAML, and a defensible unpacking plan) with analyst-in-the-loop boundaries.

re-unpacker - First Iteration Results

re-unpacker - Second Iteration Results

re-ioc-extraction - First Iteration Results

re-ioc-extraction - Second Iteration Results

Lessons Learned

Preflight checks are not optional. The fastest way to burn time is assuming tools exist and behave the same everywhere. A real “Step 0” needs to confirm what’s actually available (and which variant), before the skill starts driving commands. This also plays nicely with how Codex skills are designed to be loaded only when needed—so keeping setup predictable matters.

Design skills around artifacts, not vibes. The most useful outputs weren’t paragraphs—they were structured deliverables: hashes, strings outputs, an unpacking plan/report, and an IOC table + strict YAML. Even when analysis is incomplete, you still end up with something defensible and reusable.

Guardrails prevent accidental scope creep. “No invention,” “no live validation,” and “pause if execution is required” kept the workflows grounded. That boundary is what makes the output safe to reuse later, instead of becoming a one-off prompt result you can’t confidently cite.

Portability is the real work. The analysis logic is the easy part. The hard part is making the same playbook survive different shells, different default paths, and different tool behaviors—without turning SKILL.md into a novel. One example: rg returning exit code 1 when there are no matches can look like a failure when it’s actually “no hits,” so the workflow needs Windows/PowerShell-safe defaults.

This is where skills start to feel “real.” Once you can run the same playbook across multiple samples and get consistent artifacts out the other end, you’re no longer “prompting”—you’re building reusable procedures that compound over time.

Future Work

The next steps I’ll be looking to take this project:

Build for other AI Platforms (Claude, GitHub)

Review opportunities for dynamic analysis skills

Please feel free to add any other ideas or feedback! If you’re a reverse engineer, try these out and let me know if they’re helpful!

References:

BurntSushi. (2023, April 27). Reconsider returning 1 for “no matches” (Issue #2500) [Issue]. GitHub. https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep/issues/2500

GitHub. (2026, December 18). GitHub Copilot now supports Agent Skills. The GitHub Blog (Changelog). https://github.blog/changelog/2025-12-18-github-copilot-now-supports-agent-skills/

GitHub Docs. (n.d.). About Agent Skills. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://docs.github.com/en/copilot/concepts/agents/about-agent-skills

Mandiant. (n.d.). FLARE-VM [GitHub repository]. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://github.com/mandiant/flare-vm

OpenAI. (n.d.). Agent Skills. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://developers.openai.com/codex/skills/

OpenAI. (n.d.). Codex CLI. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://developers.openai.com/codex/cli/

Pateria, S., Subagdja, B., Tan, A.-H., & Quek, C. (2022). Hierarchical reinforcement learning: A comprehensive survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(5), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3453160

VS Code Documentation. (n.d.). Use Agent Skills in VS Code. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/copilot/customization/agent-skills

Anthropic. (n.d.). Create plugins. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://code.claude.com/docs/en/plugins

Anthropic. (n.d.). Create and distribute a plugin marketplace. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://code.claude.com/docs/en/plugin-marketplaces